Atlanta Garden

Block # 3 Signal Design by Jeanne Arnieri

Ellis Street. Peachtree Street is on the ridge with the large houses

"I have ben up to Aunties' nearly all day getting quilt scraps and doll scraps. I am right sorry Auntie is going away. I don't know what I will do for some place to run to." Carrie's diary October 6, 1864

The Southern-born Berrys had formed connections with a few other Henry County families of very different backgrounds. Amanda Berry married William Markham when she was about 20 in 1839. He was an industrious and mechanically-inclined Connecticut Yankee whose early enterprise in Georgia was clock sales, a typical Yankee occupation. Uncle Markham, who came to McDonough in 1835, imported Connecticut clocks and peddled them door to door. Amanda's brother Maxwell Rufus Berry was a business associate who tired of the road, married a McDonough girl and moved to Atlanta soon before daughter Carrie was born in 1854.

The Clock Peddler by C.W. Jeffreys,

a comic icon in early 19th-century.

William Markham (1811-1890)

They lived at Peachtree & Baker

From Gullicks and Allied Families, 1653-1948

Scholfield & Markham's Atlanta Rolling Mill produced rails, boilers and spikes for the city's transportation system.

Adolph Menze, The Iron Rolling Mill (Modern Cyclopes), 1870-2, detail

The 1860 census shows Amanda born in North Carolina,

William, manufacturer, from Connecticut and their two Georgia-born children.

What's more, when the shooting war began the Markhams continued their Union loyalties. William was acknowledged as leader among "The Unionists," suspected quite rightly of not only sympathy but also actions to aid the North. Among the Atlanta Unionists: His brothers-in-law Maxwell Berry and Thomas Healey.

Union prisoners starved and abused

Auntie conspired with other Unionist women to smuggle food and money into the city prison where captured Yankees were fed starvation diets. Carrie's aunts and uncles met secretly throughout the Civil War to plan anti-Confederate actions and so did her father. None of the men in the immediate family joined Confederate troops. William Markham went to great lengths to protect son Marcellus, 20 years old in 1861, from conscription. Marcellus finally escaped the draft by going north in the war's last year.

Southern Unionists saluting the Union flag in a secret meeting

Harper's Weekly

Atlanta's Confederate rulers knew Markham's sympathies but did little to stop or punish him, although a vigilante tried to stab him on the streets one night. One official action seems to be the 1862 seizure of Markham's 155-acre farm for a hospital dedicated to smallpox victims during the epidemic of 1862-3 when soldiers and infected civilians were held under guard there outside the city.

Dr. Edward Jenner discovered the smallpox vaccine.

Smallpox at the time was preventable with the first effective vaccine administered in the 18th century but Atlantan Sarah Huff recalled all-too familiar events:

"The people, as a usual thing, disapproved of vaccination, and also they believed in visiting the sick. For the latter reason one family between us and the city went visiting once too often, and caught the disease and spread it over the whole neighborhood. Three members of that family died."

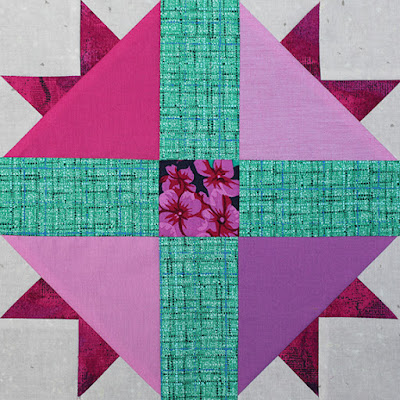

Signal Design by Dorry Emmer

Scholfield & Markham's iron mill was the South's second largest such industry, an exception to the anti-industrialism promoted by those favoring an agricultural economy.

"The Confederacy embarked on its quest for independence lacking virtually everything---save, perhaps, arrogance." Mary A. DeCredrico, Patriotism for Profit: Georgia's Entrepreneurs & the Confederate War EffortAs war demanded more iron plates for ships, more rails for trains and more cannons the mill might have ramped up production but the Unionist owners deliberately sabotaged efficiency. Confederates confiscated the mill in 1863 and blew it up in 1864 before abandoning the town.

Remains of the iron mill when Sherman's Army rode into Atlanta

When Sherman banished Atlanta residents the Markhams went north, leaving Carrie alone with her immediate family to piece quilts and doll clothes from Auntie's scraps. But after the Union victory, all returned to prosper in post-war Atlanta. No one forgot that they were Union sympathizers. The 1902 Pioneer Citizen's History of Atlanta had this to say:

Uncle William's Markham House Hotel, part of the family's postwar real estate empire.

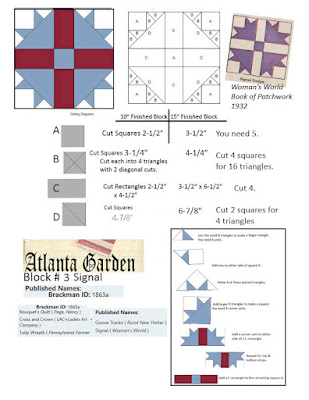

The Block

Signal Design by Becky Collis

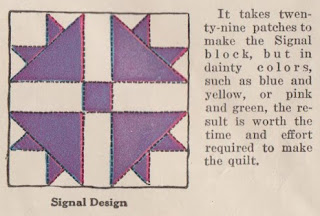

Signal Design was given the name in Woman's World

magazine about 1930.

Above the cutting

instructions for 10" and 15" blocks.

The pattern is an old favorite with several published names.

Tulip Wreath can refer to Auntie's garden in her Atlanta

home where nothing was exactly what it seemed.

Block about 1900

The alternate name Signal Design can recall the Atlanta Unionists who met at night in Uncle William's office. What kind of signals did these people use to plan meetings? Thomas G. Dyer whose book Secret Yankees details the activities of the Markhams and their associates doesn't tell us---

Kerosene railroad signal

Signal Design by Becky Brown

below. Unfortunately the author has Carrie's father Maxwell Berry's name wrong, referring to him as Madison Berry throughout, repeating an error editor Louis L Parnham made in the Pioneer Citizens History of Atlanta published in 1902.

.jpg)

4 comments:

Where could I find a clearer picture of the block and measurements?thank you 😊

I left click on the photo of the pattern. It opens in a new page. Then I right click and select "Open Image in New Tab". I open that new tab and put the cursor over the picture and a magnifier with a plus in it appears. Left click and it's more readable.

What a fascinating history lesson, I had no idea there was a Union resistance effort. And I love Ms Brown's blocks more every time I see them.

Just discovered your blog. What a fascinating piece of Civil War history.

Post a Comment